Opinion polls can’t be ‘wrong’ because they aren’t predicting or projecting anything. They are just a set of data, a bunch of numbers. Some evidence.

Just like any kind of evidence, polls need to be interpreted to make sense of them, and to weigh their significance. In other words polls are a tool that can be used in the process of making a decision, they should not be regarded as a definitive end in themselves.

Opinion polls are fundamentally limited by the fact that people who respond to them have no incentive to tell the truth. People can say whatever they want with no repercussions.

And there is never any obligation to respond to a request from a pollster, so it is quite likely that a bias will emerge where voters more inclined to vote in a particular way will also be less likely to respond, or respond untruthfully if they do. It seems probable that this occurred in the UK ’15 election, with the ‘shy Tory’ effect.

So it’s not that the UK ’15 opinion polls were totally wrong, the issue is just that people had too much faith in their results being mirrored in the actual vote. An error of analysis, more than data collection, really.

If someone tells you that they have a model that can predict the outcome of an election then they are an amateur. Only amateurs talk about ‘predicting’ something as random and chaotic as an election involving millions of voters.

Professional gamblers/investors/modellers generally distinguish themselves by using the words ‘projection’ or ‘probability’ in place of the word ‘prediction’. It may sound like a pedantic distinction, but it’s actually a critical difference that helps professionals to profit from gambling/investing activities, and condemns the majority of amateurs to making a loss.

The key word is ‘randomness’, and understanding that everything in the universe is random, except for a few immutable laws of nature.

In order to truly predict the result of an election it would be necessary to know the inner thought processes and intentions of every individual who could influence the result, plus how many ballots would be spoiled and miscounted etc. It is plainly completely unrealistic to be able to know these things, so by logical extension, a true prediction of what will happen is impossible.

Some things are extremely random, some are extremely un-random. But whatever it is, if it’s happening in the future and it is complex then it unpredictable (as in literally you cannot truly predict it). Every expression of what you think will happen in the future is therefore an estimation, a guess.

It is no more possible to predict precisely what will happen in an election than it would be possible to predict the final resting positions of a thousand marbles dropped in a cluster onto the floor of a gym hall. The forces of randomness, the many millions of tiny factors that can influence the outcome are utterly un-knowable.

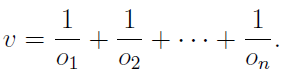

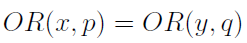

So a professional’s model will generate a range of projections/probabilities/prices/odds rather than a prediction.

Any model’s usefulness is limited by the quality of its input. In computing terminology this is referred to as GIGO – ‘Garbage In, Garbage Out’.

A ‘true prediction’ is impossible. So smart modellers embrace randomness, and acknowledge the limitations in any model of a complex event. An election model that uses polling data is automatically limited by the fact that opinion polls are a fairly weak form of evidence and therefore limit the worth of any model that relies upon them.

Some election models for general elections like those in the USA and the UK can boast of great detail by aggregating projections for all of the individual constituencies/states that make up the national result. This sounds impressive and clever, but during the ’15 UK general election some modellers allowed themselves to be seduced by their cleverness, and overlooked the inherent flaw in this plan.

The nature of general elections is that they are made up of many smaller elections, each of which happens independently. But it is a mistake to model them as though they are independent, because a single national influencing factor undetected by the polls (a party policy, a leader’s personality…) can potentially impact on them all. And because all the constituency votes happen at the same time, the model has no opportunity to adjust.

If general elections were arranged so that each constituency’s vote was held, counted and announced on consecutive days then the modelling of the upcoming constituency votes would become much more accurate, as modellers learned more about the swings in actual votes versus opinion polls. Just like a football modeller’s rating of a football team changes as the season progresses, and more relevant data becomes available.

In betting terms, individual constituencies are ‘related bets’, because a single factor can impact all of them. So it would be wrong for a bookmaker to offer the full multiplied odds on an accumulator bet on the same party in several constituencies, and it’s wrong to model them as though they had no relatedness.

If you are into election betting and modelling you will have heard of Nate Silver. He’s an American former accountant and poker player who found fame for predicting the results of American Presidential and Congressional elections. In 2012 he predicted correctly the result of all 50 States in the US Presidential election, having got 49 out of 50 in 2008.

He builds models for sports as well as elections. He thinks/models in probabilities, rather than predictions. He believes in Bayesian thinking, and in being a fox rather than a hedgehog. Which means he fundamentally doesn’t believe in making predictions. But he got famous because of his predictions.

His computer models are subject to all the limitations we have discussed above, something which was amply demonstrated when his 2015 UK General Election model bombed just as badly as all the opinion polls.

His guesses for the 2008 and 2012 US elections were probably more informed, cleverer, ‘better’ guesses than those made by anybody else. He was probably more likely to guess correctly than anyone else in the world. But they were still guesses.

So while Nate Silver deserves his high profile and success, because he is smart enough to know that predictions are futile – he became famous because of his predictions. Which were lucky guesses. This is the Nate Silver paradox.

If pollsters limit themselves to saying ‘we conducted a survey, and these are the results that we got’ then there is no problem. They are simply reporting an objective piece of evidence. Where pollsters go wrong is when attempting to present insight from their data; ‘based on our poll’s results, there will be a hung parliament’ for example.

One polling company, Survation, did get a polling result just before the UK ’15 election that showed the Tories in a 6% lead over Labour. But they ‘chickened out’ and chose not to publish it, as it seemed such an outlier – so different to all the other polls.

This is ‘herding’ – being scared of standing alone, or going in a different direction to the crowd. It is a very bad thing for a pollster to do, and anathema to professional gamblers/investors who need to have the courage of their convictions, and possess a strong streak of contrariness.

This highlights a fundamental issue with any form of analytics, which is that gathering data, and doing the analysis to divine insight from it are two separate jobs. One is objective, the other subjective. They are best kept apart, and done by different people. Pollsters should report their findings faithfully, without any comment on their ‘meaning’. It is then the job of analysts to get insight from the data.

Analytics is about finding insight from data, and using it to make smarter decisions. It is not simply ‘knowing lots of stats’.

The media loves opinion polls, because in the absence of an actual hard news story (i.e. who has actually won an election) it gives them something to write and talk about.

Polls are influenced by the media, and the media is influenced by the polls.

This is an issue because the media is not concerned with seeking ‘the truth’ about an event like an election. They are concerned primarily with being entertaining. Their job is to write/say things that engage their audience. Being accurate, fair, balanced, reasonable and analytical are lesser considerations. The media should not be trusted to interpret the data of opinion polls. They have no real incentive to do it well, and they probably don’t have the ability to extract the smart insight from them anyway.

Opinion polls aim to get a representative sample despite only asking the opinion of a tiny minority of the actual electorate. So there is always going to be a considerable margin for error. But that doesn’t stop media outlets pouncing on poll results and making a headline of such insignificant and random variation as a 2/3% shift to some party.

This is represented as a ‘swing in the polls’, but in reality is nothing of the sort. The sample sizes are far too small, and the inherent problems with polling methods too large to be sure it is signal not noise. And anyway, these polls are generally simulating a nationwide vote that will never actually happen. National elections are based on constituency/electoral college totals, not the popular vote, and are generally ultimately decided by a relatively small number of ‘swing’ states/constituencies.

Compared to the task of modelling elections, football modellers have the considerable advantage of being able to use loads of high quality, relevant, recent data – because football teams play lots of games. We can watch the games, and/or gather stats from them. The teams are usually trying their hardest, so it’s relatively easy to get a decent idea of their innate level of ability.

But elections are much less common than football matches. If there was a general election every month, then election modellers would undoubtedly do a much better job of projecting election results. But in the place of actual elections, they are forced to instead use opinion polls and results from previous elections held years and even decades in the past.

To compare it with football modelling, using opinion polls to model an election result is like using the evidence of football club training sessions to model a football match. It isn’t terrible – you can get a reasonable idea of how good a football player/team is from watching him/it train. But it will never be as good as the real thing. So nobody should be surprised that the results of election models aren’t great.

Pollsters and political commentators spend a lot of time thinking about politics. But for many members of the voting public, politics is a bit boring and they will only really start to consider how to vote (if they vote at all) on the eve of an election. So opinion polls that are conducted closer to the polling date are better than polls conducted a long way out from an election. This is something those in the ‘political bubble’, or modellers who crave data for their models can fail to recognize.

One of the great challenges in assessing an upcoming election, especially if you plan to build a model around it, is to properly understand the rules of the game.

How the votes are distributed is as/more important than the actual numbers of votes cast. For example it has happened four times in US election history that the President of the United States gained the White House despite a rival getting more overall votes.

A good example of election analysts failing to account for the rules of the game was with the recent UK Labour party leader election. The largely unconsidered Jeremy Corbyn only barely scraped into the field of candidates, and would have head no chance of winning had the leadership election been based on votes cast by Labour MPs.

But a change in the leadership election rules that allowed all party members a vote saw the outsider sweep into the job, having at one point been 100/1 with UK bookmakers. They hadn’t properly researched the rules of the game, and/or understood their significance.

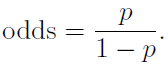

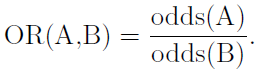

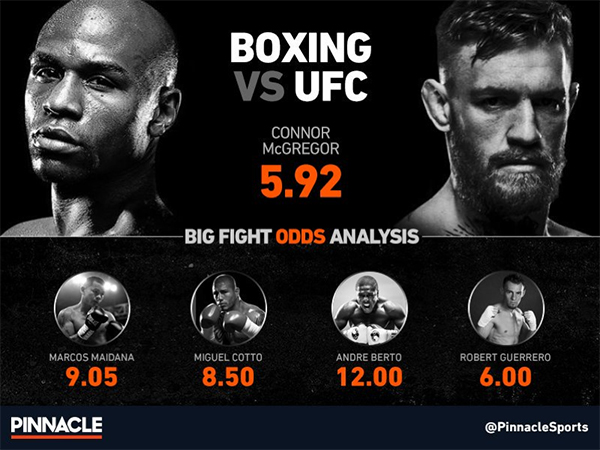

In every modern election cycle, bookmaker’s betting odds on the outcome are cited as evidence by pundits in the media. In principle, using betting markets is a fine way to get to accurate projections of what will happen in future complex events. There are some very sound reasons why betting markets can be better than opinion polls.

Firstly, the contributors to markets have some ‘skin in the game’ through the investment of their own money. They are incentivized to think about the outcome, and to act with care and attention, unlike poll responders who are free to say whatever they like with no consequences.

Betting markets benefit from the ‘wisdom of crowds’, where the aggregation of individual opinions comes together to make a smarter opinion than that of any individual. In recent times this has been harnessed to further science, where betting markets have been used to gauge the worth of academic scientific studies.

The act of betting on an election is done after the analysis and interpretation of the raw data, including polling numbers. So all the players in an election betting market are analysts. They will differ wildly in the amount and quality of analysis they will have undertaken, from detailed examination of polling data and previous election results on one hand, to gut instinct based on conversations in the pub on the other. But not every member of a crowd needs to be wise in order for the crowd to have wisdom.

In some cases betting markets become very wise indeed, and following them will lead to the most accurate projection of likely outcomes it is possible to get. Examples would be the Betfair market on a big horse race at the ‘off’, or the Asian market on big football games at kick-off.

The key ingredients in making these markets so smart are a) their liquidity – i.e. there is so much activity going on in the market that Darwinian forces are applied that force it towards maximum efficiency, and b) the quality of the analysis that is undertaken by the dominant shapers of the market.

Smart professional gamblers and syndicates using analytical models and ratings to seek inefficiencies in these sports market based on their own very accurate projections of ‘true’ prices. This knocks the prevailing market price for an outcome into very efficient shape.

These forces are not at play in election markets however. Election markets are not liquid. Compared to major sporting events, very few people actually bet on them, and don’t bet a lot of money when they do. For bookmakers, election markets are mostly about PR. It is an opportunity for them to seek free advertising by getting their names in the papers and on the TV in the ‘News’ sections, where they normally cannot reach.

The way horse racing and football prices evolve is that the bookmakers make their initial estimations of likelihoods by publishing their prices, and these progressively get shaped and adjusted by the weight of money as customers (including the pros and the syndicates) place bets. The initial bookmaker prices will be pretty good to start with as they have decent expertise in setting these prices, and then the ‘wisdom of the crowd’ will be considerable.

But in the case of election markets the bookmakers have little or no expertise, so the initial prices are often little better than wild guesses, put together by the PR guys rather than professional odds-compilers.

The number of bettors in an election market who are capable of doing quality analysis to project accurate true odds of the outcome in all the constituencies/states, and therefore the overall election outcome, is tiny compared to the number of experts in horse racing and football. So the crowd is much less wise, and the market therefore much less to be trusted.

It is possible to use betting markets to get an insight into elections, but you really have to know what you are doing, and know where to look.

In the US at the moment the two main parties are in primary season, and (if you hadn’t noticed) the media coverage is being dominated by Donald Trump. He is as short as 11/4 (26.7%) to be the next US President. Even without building any sort of model, we can tell you that the real chance of Trump winning is much, much less than 26.7%. He should probably be nearer 50/1 (2%). Donald Trump is a good case-study of a lot that is wrong with election analysis.

Trump is currently going well in opinion polls. But the actual US general election is just under a year away. Polls this far out are significantly worse predictors of election outcomes than those closer to the date. And as we saw in the UK ’15 election, even polls conducted a mater of hours before the polling stations open can be way out. Don’t be fooled that long-range opinion polls are significant, just because the media tells you that they are.

Trump’s current situation is a media creation. He has a bit of charisma (this is undeniably true, no matter what you may think of his policies) and is a known name and face from his appearance on a popular TV show (US Apprentice) so has instant name recognition with everyone who is asked an opinion at this stage.

But many voters will not really have made their mind up about a preferred Republican nominee yet, never mind their choice of a Presidential candidate. Voters are much less vexed about the General Election this far away from the day than the journalists and pollsters whose job it is to generate interest in political stories.

The rules of the game Trump is playing really matter here too. For him to become President he (realistically) needs to win the Republican nomination, and this is a process in which behind-the-scenes political manoeuvring is common-place and influential. So if the Republican establishment decides it doesn’t want Trump as its candidate then he’s very unlikely to become their candidate, even if his popular support manages to hold up (which it probably won’t).

But it’s very unlikely Trump can win the Republican nomination anyway. The rules governing the electoral process of finding a Republican nominees are complex, but have a built in disadvantage to candidates like Trump who are very unpopular in Democratic leaning constituencies.

And even if Trump does manage to secure the nomination, and even if he doesn’t get trounced by Hillary Clinton in the Presidential debates and campaigning, there is still the ‘when push comes to shove’ principle.

On the morning of polling on November 8th, if Trump really is the Republican nominee then millions of Americans are going to ask themselves ‘do I REALLY want to see Donald Trump as the next leader of the Free World?’.

is the (constant) profit from the strategy and 1 is the unit vector.

is the (constant) profit from the strategy and 1 is the unit vector.

for which the expected return from runner

for which the expected return from runner is negative’, and the corresponding sum on the bottom means ‘add all values of

is negative’, and the corresponding sum on the bottom means ‘add all values of for which the expected return from runner

for which the expected return from runner

is the total amount staked in the pool (i.e., the pool size);

is the total amount staked in the pool (i.e., the pool size);

has a value of sqrt (0.9*$413/ 1-(0.9*0.56)) = 23.77.

has a value of sqrt (0.9*$413/ 1-(0.9*0.56)) = 23.77.